# 5 Is the power of love enough to shift our fixed mindset on inclusion?

In short, the answer to this question is no.

Most staff working in schools love the children and the community they serve. This is my experience as both someone who worked in schools for over a decade, and as someone who now visits a wide variety of schools on a regular basis. But the power of love is indeed, a curious thing.

Every so often, I notice either in myself or others, a throwaway comment, a well-intentioned acceptance of a lowered standard or a poorly implemented practice, which suggests that sometimes lurking beneath the love is something a little murkier. And these microaggressions seem to show up most often when discussing those with the greatest need, i.e. pupils with a special educational need or disability.

When I’ve reflected on my own practice and comments I’ve heard, I’ve wondered whether they originate from an unconsciously harboured deficit mind-set (‘this group of children just aren’t that aspirational’) or whether they represent an exhausted giving in to judgemental frustration (‘it’s not a SEND problem, it’s a poor parenting problem’).

Once outside of a school setting, and the day-to-day pace of school life, these moments are easy to spot and critique. However, they are notoriously hard to unpick in real time. No matter how much you ‘care personally and challenge directly’ (thanks, Kim Scott), calling into question a colleague’s commitment to or efficacy in supporting the most vulnerable students, is tough on both parties.

This is why we have spent time this term reflecting on our own mindsets regarding SEND and how we might support colleagues to do the same. Our learning in this area had two main stimuli.

Firstly, our second guest speaker at day three in Birmingham was Tom Rees, CEO at Ormiston Academies Trust. We specifically invited Tom to speak to our congregation of over 80 aspiring headteachers from all four regions, to speak to his 2023 CST paper ‘Five Principles for Inclusion’.

Some stand-out messages from this that have caused pause for thought include;

Firstly, according to this 2021 EPI report from Jo Hutchinson, currently around four in 10 pupils within the school system will be classified as ‘SEND’ at some point in their school journey. This begs the question about whether the medicalised model ‘locates problems within children, rather than within approaches to teaching them.’

Secondly, why is it still common practice to place children with SEND ‘at the bottom of the educational hierarchy’, with the least expert members of staff? There are schools thinking creatively about this (double staffing at Dixons is pretty special) but there is certainly room for more innovation here.

Finally, we were pushed to challenge the narrative that this is simply a ‘system’ issue; we are the system; ‘there is scope for everyone working at every level in the education system to learn more, and to improve provision and outcomes’. What training and support do site staff, ECTs, middle and senior leaders, as well as governors and families need to ensure that all pupils can thrive?

Just a few weeks after this, cohort member Laura Moyse hosted a visit to her special school (Hob Moor Oaks, part of Ebor Academy Trust in York). This is the second of three possible visits during this year’s programme to specialist settings, a marked increase from the one we visited last year. In the eleven years I worked in schools, I never made time nor felt I had capacity or permission to visit a special school or an alternative provision and my practice was undoubtedly worse for it. The exposure to the incredibly high expectations and high support on offer in these environments has been a highlight for many on the programme;

Seeing a special school was so important. It brought home the commonalities between us and how powerful collaboration should be across sector, especially for amplification of the voice of SEND.

Portia Taylor

Shona Morgan (Ebor Academy Trust SEND lead) and Laura provided us with insight to their detailed curriculum planning;

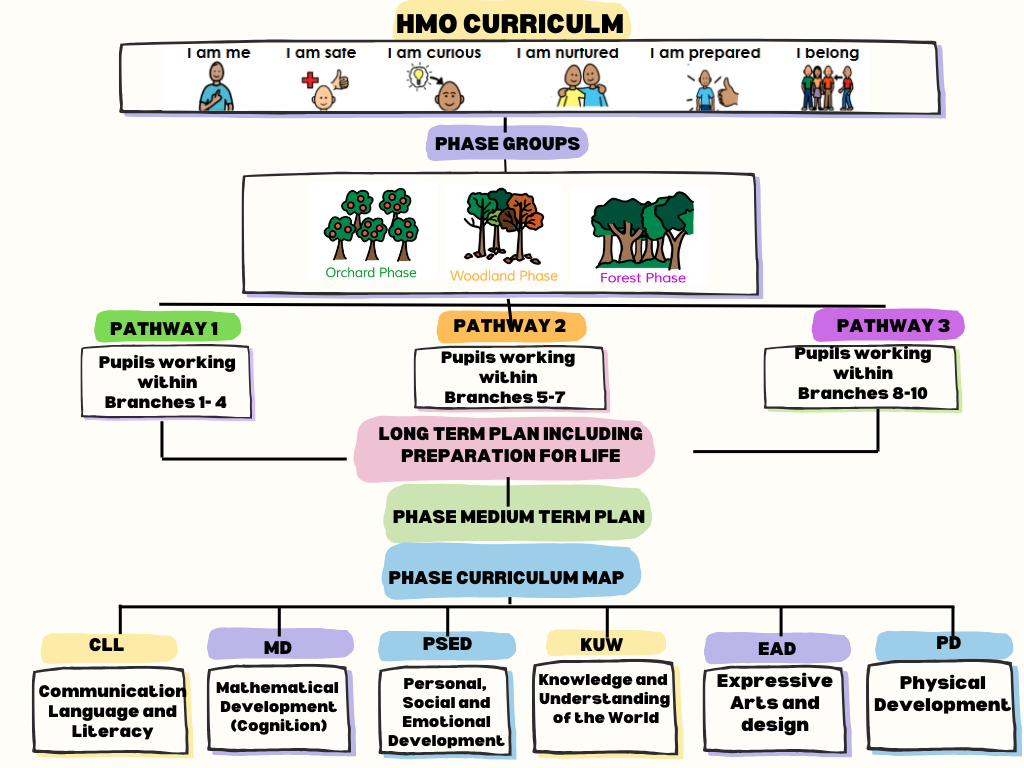

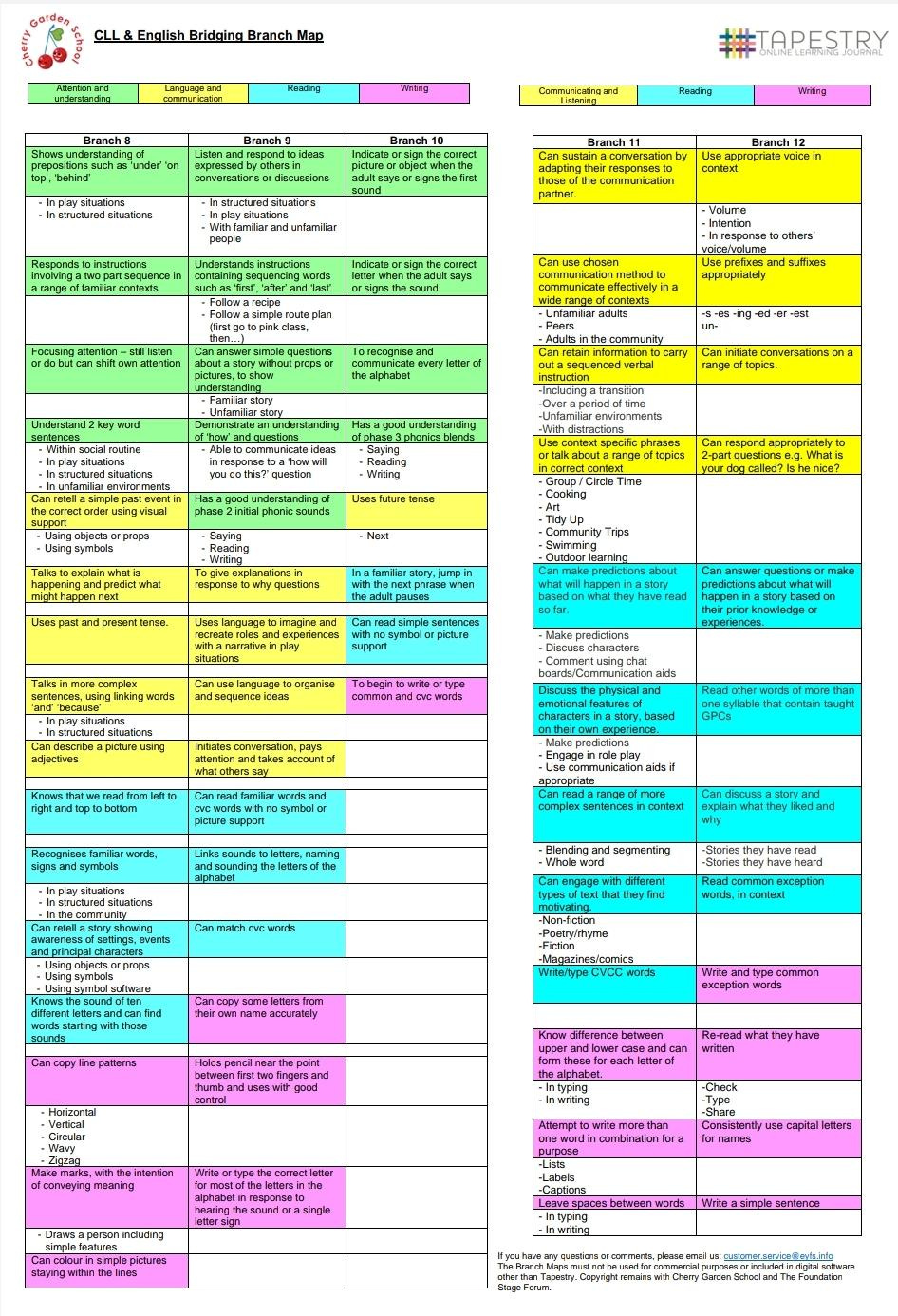

Using Tapestry, they have identified three pathways, and within that 10 ‘branch maps’ (created by Cherry Garden School). We loved how asset-based it is as a model, celebrating the milestones that children have reached and acknowledging that progress is rarely ‘linear’.

They also shared their experience of writing and enacting EHCPs; something that many in mainstream didn’t feel was a strength.

During our tour of the school, we witnessed first hand an example of what Tom Rees was referring to when he spoke about the inclusion principle of being ‘different, but not apart’. Given the co-location of HMO with Hob Moor Community Primary Academy, a mainstream school, both cohorts of children grow up together and appreciate each other’s differences as well as their similarities.

Our main reflections on inclusion this term have been that we can’t continue to ring our hands and profess to caring deeply about the SEND crisis. We, the system, need to act strategically to ensure practice improves in this area. This might look like re-making the case to our teams about the importance of high quality SEND practice, it could be refining and updating what great SEND practice looks like in our settings, or it could be measuring the impact of current practice through greater SEND pupil and parent voice. Whatever we do, we know we can’t just rely on the power of love.